The rebuild: Autumn 2000 – a beginning

The ravages of time

I live by the sea, and the salt-laden air took its toll. In the autumn of 2000, after six years of ownership, the Le Mans was starting to fall apart, and I’d stopped riding it as the fork stanchions had rusted badly. Eventually I took it to Wessons to get the forks repaired, and found Steve Wesson putting the finishing touches to his Moto Guzzi special. I rashly decided to ask Steve if he’d build a Le-Mans-based special for me. At that time Wessons was partway through moving, and the shop had relocated to Horam, 25 miles away; however, the workshop was still in Brighton, where it would remain for several months. Because of the move, Steve was unable oversee my project, but made a very generous offer: if I was willing to supervise and do most of the work myself, he’d let me build my special in Wessons’ workshop, if Gary, the mechanic, was happy with this arrangement. Gary had no objections.

The plan

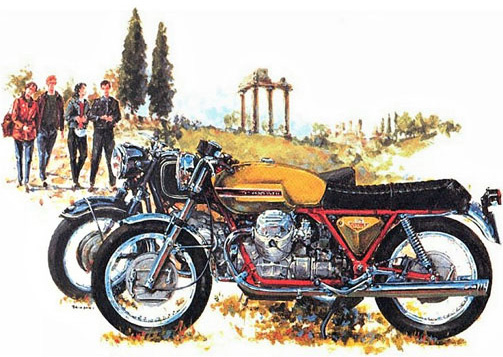

I wanted every worn and corroded part replaced; I wanted my Le Mans to look like new. But I also had further plans for the bike: it had to handle, brake and perform like a modern machine; it had to resist corrosion by the sea air; and its looks had to be improved – I’d decided it would be recognisable as a Le Mans I but with a touch of the classic 1960s British cafe racer (Figure 1).

I carefully drew up a plan of action, and made a long list of things to do and buy. (The summary lists the changes and modifications in detail.) I also rooted around the stores at Wessons’ workshop for anything I thought might be useful – Wessons was a Moto Guzzi treasure trove back then, as they used to break and sell parts from Guzzis going back to the 1950s. A few days later, I rode the Le Mans into Wessons’ workshop to start the rebuild.

Being a hard-used 20-year-old bike, a huge number of things were worn out or damaged; I even found out that the crankcase hand been glued together at some time!

Figure 1. The Moto Guzzi V7 Sport (produced from 1972 to 1974) - the company's first V-twin sport's model. The look of my custom Le Mans harks back to this classic motorcycle.

Aesthetics

The various engine cases, the bevel drive box and the carburettor bodies were sent to Camcoat to be carefully sandblasted and coated in clear ceramic, to protect the alloy from corrosion. Camcoat were also sent the stainless-steel exhaust pipes and silencers to coat in satin black ceramic.

Meanwhile, piles were made of items to be chromed, painted and powder coated, and these were sent respectively to London Chroming, Pageant Paintwork and Triple ‘S’ Powder Coating. I wanted a Le Mans I petrol tank, but the only one I could find was badly damaged. Pageant Paintwork commissioned Competition Fabrications to repair it, and they did a superb job, completely refabricating the lower third of the tank.

I tried various aftermarket seats, none of which fitted well. Eventually I bought a Corbin seat, which despite being the most expensive, didn’t fit either! I ended up modifying the Corbin seat myself, carving the foam to shape.

Tuning the engine

The engine was to be tuned for tractability and acceleration rather than for top speed, and I decided on the following changes: an increase in capacity from 844 to 949 cc, stage 1 gas-flowed heads with a lead-free valve conversion, a Raceco SS2 camshaft, a balanced crank assembly and a high-performance exhaust system. The 36 mm carburettors would be kept but gas flowed, as larger carburettors move the peak power higher up the rev range, which I didn’t want.

Improving the braking

The standard Brembo brakes aren’t bad, but like much else on the bike are inefficient compared with modern equipment. I noticed that Wessons had an unwanted pair of four-pot Brembos and discs, as used on recent Ducatis and Moto Guzzis. Gary, the mechanic, found a two-pot Brembo Goldline rear caliper amongst Wessons’ second-hand spares, which we used so that all the brakes would be the same colour. (A quick aside: I’d delinked the brakes years ago as I don’t like the idea – I want full control over my brakes, especially in slippery conditions!)

Improving the handling

Despite the plaudits lauded upon it in the 1970s, the Le Mans doesn’t handle that well, although better than most of its contemporaries: the suspension is harsh, and the bike needs to be wrestled around bends, which is exhausting. I decided to try improving the handling by changing the wheels and suspension.

The new wheels were to be wider than standard to allow modern, wide, low-profile radial tyres to be used. The front rim would also be 1 inch smaller in diameter than standard to quicken the steering; and the rear rim offset would be increased by 5 mm to allow the wide tyre to clear the swinging arm. I chose wire-spoked stainless-steel wheels for their looks and corrosion resistance, with hubs taken from an old wire-spoked Moto Guzzi T3. The front tyre size is 110/80 × 17 inches, and the rear 130/70 × 18 inches.

I’d replaced the standard forks a few years earlier with a pair of Marzocchi Stradas dating from the 1980s, and although better, they are still awful compared with modern forks. I decided to commission Maxton Engineering, the race suspension specialists, to modify my forks and supply a pair of custom-built rear shocks. Maxton did a superb job, replacing the complete Marzocchi internals with their own.

The Marzocchi forks, front hub and brake discs are incompatible, and the only solution was for one-off bearing carriers (on to which the discs bolt), caliper brackets and wheel spacers to be made. These were machined from stainless steel by an engineer friend, Stuart.

The rebuild

So far only one thing had gone wrong: to save time I’d asked a local company to powder coat my fork legs. Unfortunately, they dropped one and broke a part off. As Marzocchi Stradas are no longer made, it had to be repaired. After 6 weeks of waiting for the powder coaters to repair the fork leg, I gave up and got the legs back. It was easy to get the broken leg welded, but machining the weld took some time as no-one had a lathe large enough to hold the leg: I eventually found a local ship repairer that had the biggest lathe I’ve ever seen.

Once Gary and I had got all the various parts back, and I had ordered all the stainless-steel bolts, nuts and washers we needed, we started the rebuild. A few one-off items, mainly brackets, were also needed, and Stuart made these for me in stainless steel.

Gary concentrated on rebuilding the engine, gearbox and bevel box. To increase reliability, we added a Raceco ventilated sump extension, Raceco high-performance valve springs, alloy timing gears, and a Le Mans V deep oil filter and union. The triangular carburettor tops were replaced with flat tops, and weaker slide return springs used, to lighten the throttle action. Venhill Teflon-lined low-friction throttle and clutch cables were also used.

Meanwhile, I rebuilt the chassis, using parts from various Moto Guzzi models, some of which I modified. I also bought a number of after-market parts, such as Harris Performance clip-ons, an Ohlins steering damper and a 1950s Wipac rear light unit. One important change I’d made long before the rebuild was to replace the side stand with one from a Triumph that worked: the original Le Mans side stand flips up once the bike’s weight is off it – my bike has fallen over several times because of this!

Once the engine was back in the frame, I started on the electrics. An Odyssey sealed gel battery and Lucas Rita electronic ignition were used, and the switches replaced by a right-hand Yamaha unit. I decided the original wiring harness was a mess, and rewired the bike from scratch using waterproof connector boxes. For reliability, the Bosch alternator was replaced with one made by Saprisa, as used on later Moto Guzzis.

Autumn 2000

Autumn 2000